In this series, we examine how Umberto Eco’s book, ‘How to Write a Thesis,’ can be used to help writers improve their focus, research smarter and get any writing project done faster. In part two, we look at strategies for creating a work plan using a tree diagram.

Though Umberto Eco’s newly English-translated book, How to Write a Thesis, focuses on the thesis as its main concern, in truth, it’s a handbook for any writer hungry for techniques and skills to investigate a topic for a long-form article or ebook.

How can diagramming help writers organize thoughts into different logical approaches? How can questions create a succession of hypotheses and lead to their rigorous investigation?

Diagramming and leading questions based on work plans

When given an assignment, writers open up a blank Word Doc and stare at the daunting white screen and the blinking cursor, waiting for words to come forth from a muse.

But thought isn’t locked in word-processed-blocked-type font. Some of the best writers take pen to paper and map out their mind first.

Eco encourages writers to start with a work plan. Work plans can be described as outlines, mapping and/or ways of organizing thoughts strategically.

Basically, Eco emphasizes that before you start any serious writing project, you should know the aim, while also leaving yourself open to the discovery one gets from the act of writing, researching and investigating.

There are many approaches to choose from:

- A chronological plan: (historical thesis, such as “The Jim Crow Laws in the American South from post-Civil War”)

- A cause and effect plan: (“The Causes of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict”)

- A spatial plan: (“The Distribution and Geographical Reach of Netflix”)

- A comparative-contrastive plan: (“Nationalism and Populism in Europe During World War II”)

- An inductive plan: (move from evidence to the proposal of a theory)

- A deductive plan: (begin with the theory’s proposal to possible application to concrete examples)

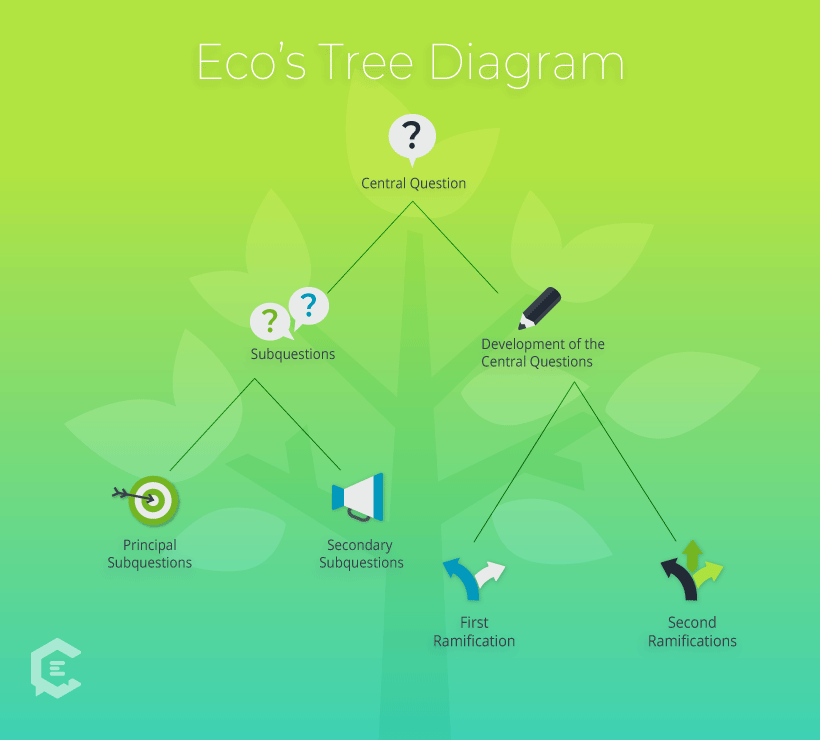

In this chapter on creating work plans, Eco introduces a writing structure and also represents it as a “tree diagram.”

The tree diagram has several parts: the central question, which branches out to subquestions, and each of those branches have ramifications. Every writer starting a piece needs to be asking themselves a central question. This central question, by virtue, must be a question that society as a whole would ask in the collective “we.”

It has to be a question that many people are asking. From this central question, or leading question, other subsequent (or subquestions) filter through and those questions come as your investigation of the evidence you find gets more detailed.

As for the ramifications, most societal solutions are not in themselves complete and flawless solutions. Each solution has within it ramifications, results that emerge because of a set of decisions that were made.

Below is a diagram of Eco’s tree diagram.

Wither in the writing world: a test of the tree diagram

To test Eco’s structure and tree diagram, I read the August 2019 issue of Vanity Fair to see if any of the long-form essays in that month’s magazine in any way used one of Eco’s suggested work plans to address an issue.

Of all the articles in that publication, Bethany McLean’s exclusive interview and story titled “Bitter Pill” with David Sackler, heir to Purdue Pharma, came the closest to using the structure of Eco’s tree diagram.

In the article, McLean poses the central question:

- Did Purdue Pharma and the Sackler family knowingly create the opioid crisis, currently devastating America?

Her subquestions go from theory to evidence and its ramifications:

- Did the family make choices in over-marketing OxyContin’s safety?

- Did the company rely on limited evidence of the drugs’ potential harm?

- Once the epidemic was evident, did the company do enough to curtail prescriptions and stop pill dispensing doctors?

Admittedly before I even read the full article, I already knew what was going to happen: Sackler says the family didn’t know the drug was dangerous back then; nor did they know that it would set off an epidemic; nor are they culpable.

However, because of the structure McLean chooses, she engages the reader on a ride where we know the end, yet we are willing to go along with her narrative that explores David Sackler’s narrative. McLean gives us some new, and old information, but more importantly, her writing makes us look at bigger questions and ask us to wonder if the FDA and the pharmaceutical companies hold profits higher than public health.

In developing a logical work plan, as a writer, you can explore evidence and call to question larger issues that could provoke your readers into action.